FLYING THE FLAGSHIP

It was to be Britain’s most iconic boat – a floating showcase sailing around the world drumming up post-Brexit trade. It was also shipbuilding’s biggest and most complex competition. Kate Lardy talks to the finalists of the ill-fated national flagship programme – shelved last autumn due to government cuts –and finds out if there is any hope of a resurrection

It started with the best of intentions. The proposed national flagship was to be the “jewel in the crown” of the government’s new shipbuilding strategy, said defence secretary and shipbuilding tsar Ben Wallace in July 2021. It was not, as some of the press called it, a new “royal yacht” and replacement for HMY Britannia, now docked in Edinburgh as a tourist attraction.

Its primary function would be to boost trade and drive investment into the British economy by hosting exhibitions and trade fairs. It would also be a diplomatic tool, voyaging around the world to entertain and accommodate dignitaries and heads of state as a floating embassy. Moreover, the ship would be built in the UK by British artisans, showcasing their skills and expertise with leading-edge technology, to be, as Wallace pronounced, “the greenest ship of its kind”.

Royal Yacht Squadron member Ian Maiden had been advocating for this long before prime minister Boris Johnson first announced the programme on 30 May 2021.

The lifelong sailor and successful businessman has been passionate about it since the Royal Yacht Britannia was decommissioned in 1997, and even went as far as commissioning the late, great yacht designer Jon Bannenberg to draw a concept to succeed it, but he has always and purposely avoided the nomenclature “royal yacht”.

He was struck by the fact that £3 billion in UK trade deals were signed off on board Britannia in her last three years of service. “That was a very significant thing because the yacht was never intended as a sales platform. And it occurred to me at the time that because we’re a maritime nation, it seemed sensible to have a custom-built ship for trade promotion,” says the fiercely patriotic Maiden. “There’s a tendency in Britain not to be proud of ourselves, and we should be proud of our achievements.”

GEOFF PUGH - SHUTTERSTOCK

GEOFF PUGH - SHUTTERSTOCK

"There’s a tendency in Britain not to be proud of ourselves, and we should be proud of our achievements."

Lifelong sailor and businessman Ian Maiden was an early advocate of a custom-built ship for trade promotion.

Maiden was perhaps the driving force behind the competition. “I was the first one that got Boris Johnson to take it up. I kept on pestering him,” he says. Maiden had used the term “national flagship” and the build estimate of £200 million to £250 million in his letters to the prime minister before Johnson announced a vessel of the same name, which was later given a budget of the same amount. Coincidence? He doesn’t think so.

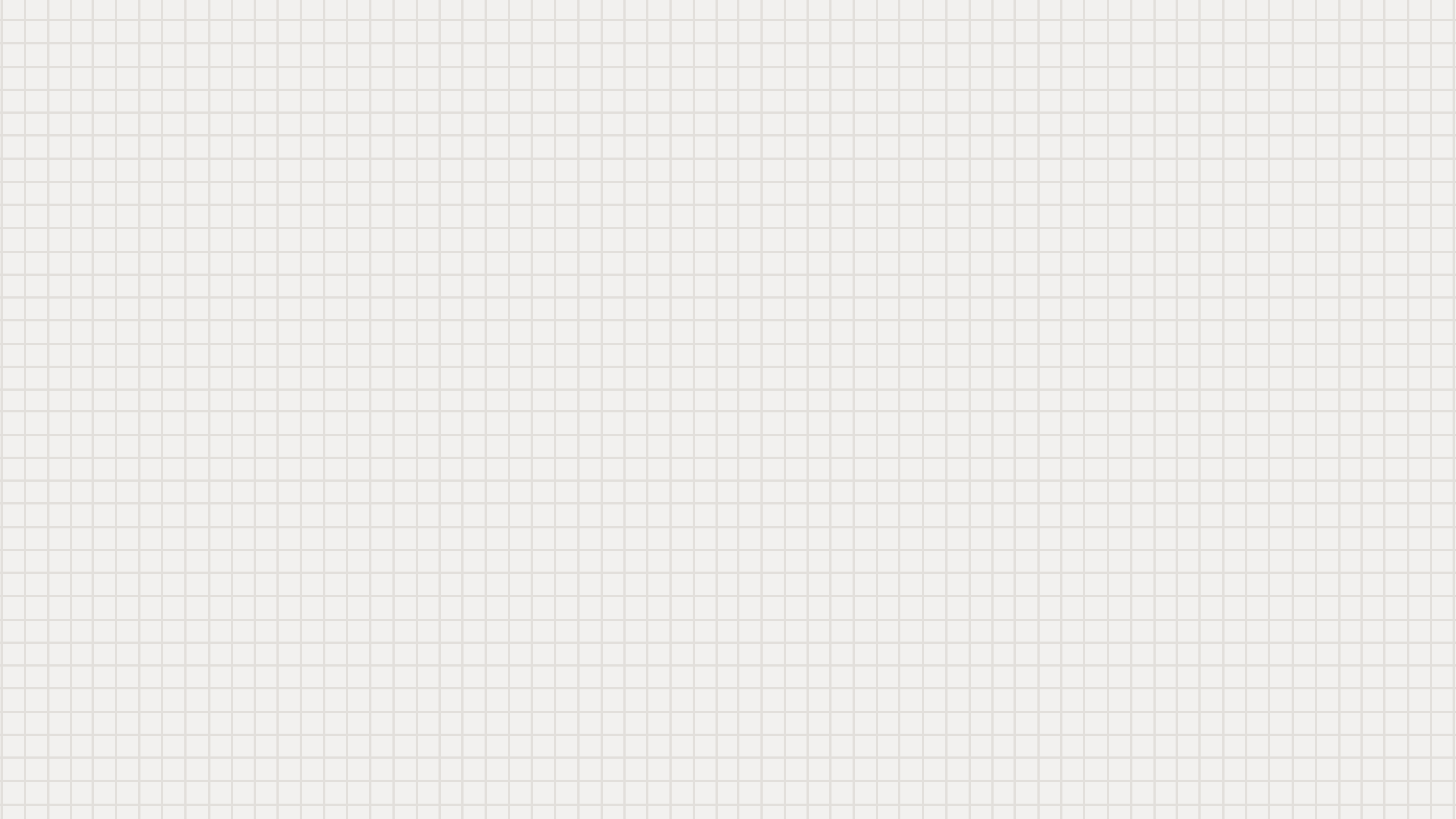

He is quick to point out that the flagship would have a cachet for diplomatic meetings and trade fairs that far eclipses any five-star hotel, putting it in an excellent position to harvest the demand for British exports from fast-growing Commonwealth economies. “For example, India has a vast new middle class that is almost as big as the whole of the British population… I could see the ship in Mumbai, the Band of the Royal Marines, floodlights, red carpet and the president of India on board, followed by a sea day. That degree of commercial impact is unavailable in a land-based venue,” says Maiden.

STU - ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

STU - ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Under World Trade Organisation rules, bidding for the project would typically be open to international yards, but there’s an exception for ships built for defence. So the national flagship, although essentially a passenger ship, would have an element of defence to it, overseen by the Ministry of Defence (MoD), crewed by the Royal Navy and built by a British shipyard. Although exactly how it would be used for defence remains highly confidential, protected by strict non-disclosure agreements with all parties in the design competition.

Twenty companies – builders, designers and naval architects spanning the commercial, military and superyacht industries – responded to the pre-qualification questionnaire and were deemed eligible to bid. Then, after learning what the process would entail, some dropped out. It was to be a tremendous amount of work done free of charge, as the MoD was not funding any of the bids. The period allotted between the MoD’s feedback for the preliminary design work and the deadline for the full bid was particularly compressed at just over two months, during which time thousand-page-plus submissions would have to be prepared. The only way forward was to join forces to form consortiums and divvy up the immense workload. Ultimately, four teams, each made up of a core group of companies and supporting players and revealed over the following pages, made complete bids.

The competition was far from a beauty contest. In fact, convening the aesthetics panel was to be one of the last steps in deciding the winner.

The competition was far from a beauty contest. In fact, convening the aesthetics panel was to be one of the last steps in deciding the winner. Firstly, the teams had to prove they could handle the technical requirements, providing detailed structural drawings and stability analysis early on. For those accustomed to the commercial world, “the process seemed a little bit back to front,” says Nick Roe, project director for the consortium Team New Flagship Company, who used to project manage new-build ships for Carnival.

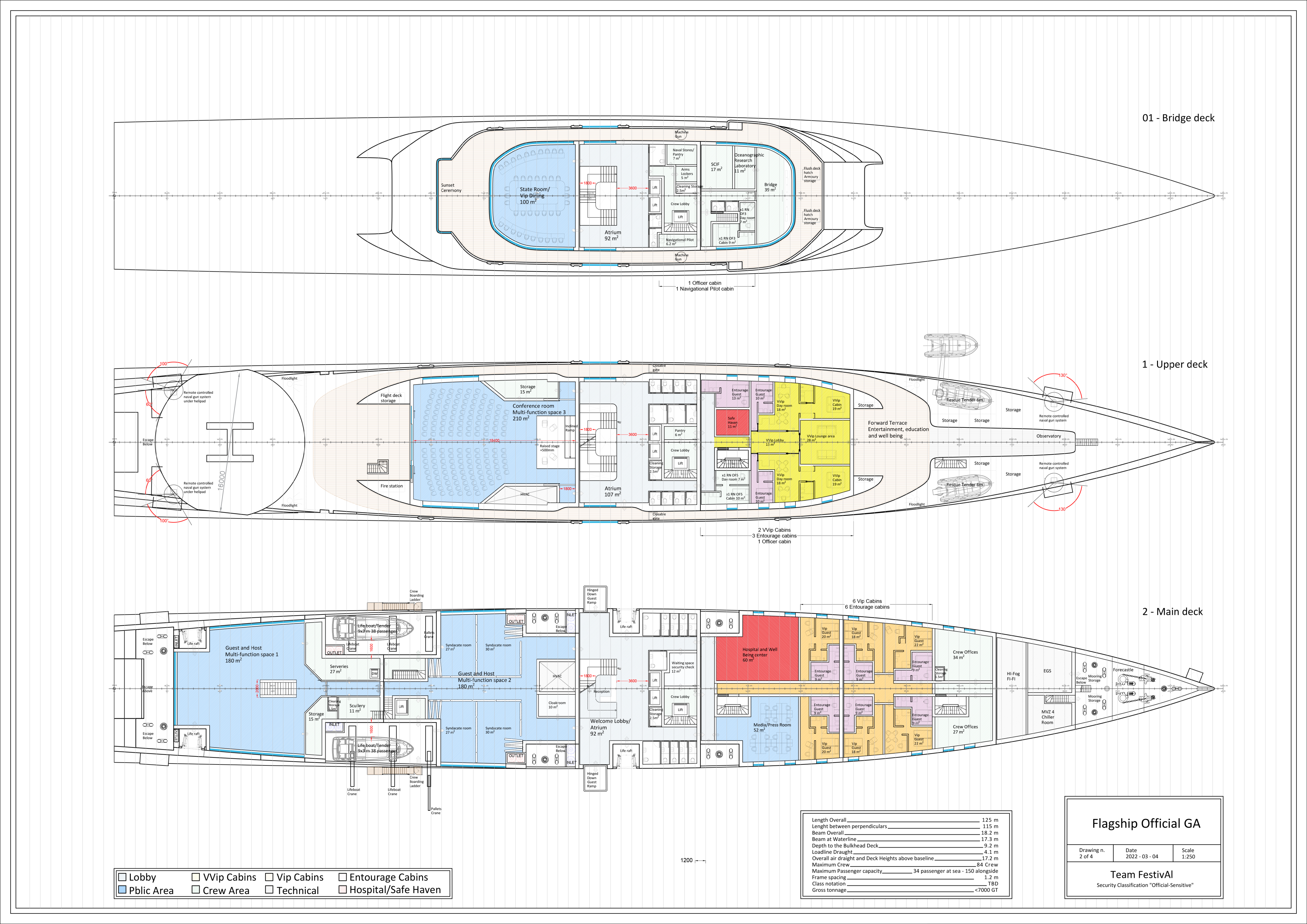

The designs needed to sleep at least 36 passengers, including unspecified “VVIPs”, and 52 Royal Navy crew, as well as take 256 guests to sea for short voyages. The public spaces on board had to be able to host conferences, trades shows, banquets and receptions – perhaps simultaneously, with an underlying and complicated choreography that would not have the various parties on board crossing paths.

The judging used a points system. “There were the must-haves, such as the exhibition and conference space, a sizeable reception room and meeting rooms, but also separate security routes for VVIPs that didn’t conflict with the routes other attendees would take.

In addition, there were aspirational elements, like more space for the Royal Marines Band. You scored on every single point. You had to have the must-haves, and any of the aspirational things, like extra cabins or another exhibition space, would give you extra points,” explains Stephen Payne, consultant for Team Harland & Wolff, whose team, like Team Signal, racked up points by accommodating 42 extra support staff on board. “You had to demonstrate that you could properly accommodate 200 people in various scenarios, but for every three extra people, you got an additional point,” adds Dickie Bannenberg of Team Signal. “The scrutiny of it, the assessment of it… there’s just no equivalent in yachting.”

"This is probably the most complicated design project any of us have ever been involved in"

All of this had to be wrapped up in a design that illustrated the themes of diversity, heritage, flexibility, sustainability and ingenuity. “I’m sure that all the people who went as far as we did would agree that this is probably the most complicated design project any of us have ever been involved in,” says Mark Whiteley, co-designer of Team New Flagship Company’s bid.

One glaring omission in the MoD’s copious documentation was any reference to the royal family. Yet the press still latched onto the idea of a royal yacht, which fuelled critics’ objections and polarised the project. With a cost of living crisis unfolding, the vessel’s £250 million build cost that was estimated by the MoD appeared wasteful to opponents, while proponents championed the jobs the build and trade fairs would create. Amidst political upheaval within the Conservative Party, the programme was ultimately suspended on 7 November 2022, with an announcement from Wallace that the Shipbuilding Office would prioritise the build of two Multi-Role Ocean Surveillance ships in light of Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

With the competition terminated, the teams are now able to lift the shroud of secrecy that surrounded their designs. Here they each reveal – as Maiden puts it – “an oven-ready design for the superyacht market”.

B&R

B&R

KENNY LAURENSON

KENNY LAURENSON

Dickie Bannenberg and Simon Rowell

TEAM SIGNAL

CORE MEMBERS

Interior and exterior design

Bannenberg & Rowell Design

Naval architecture/regulatory compliance/engineering/technical design Houlder

Technical consultant/security

Frazer-Nash Consultancy

Glass engineering Eckersley O’Callaghan

SPECS

LOA 140m

Gross tonnage 11,200GT

Team Signal’s project is nothing like its competition’s.

“This is very obviously and deliberately not a Britannia nostalgia-fest with a blue hull and buff funnel or any derivation thereof. It belongs much more in the naval family,” says Dickie Bannenberg of Bannenberg & Rowell Design. He and partner Simon Rowell (both pictured right) interpreted the MoD brief’s veiled comments about aesthetics to mean that it was looking for something unlike anything else afloat.

“Absolutely nowhere, in any brief at all, did it say this should look like a passenger ship or cruise ship or royal yacht or military vessel. So, what that said to us is this is an entirely unique vessel with an entirely unique brief – it should look entirely unique,” Rowell says.

The well-regarded superyacht design firm teamed up with Houlder and Frazer-Nash, which both have extensive experience working with the Ministry of Defence. The pairing paid off as Team Signal was among the final two contestants, along with Team Harland & Wolff.

"This is an entirely unique vessel with an entirely unique brief – it should look entirely unique"

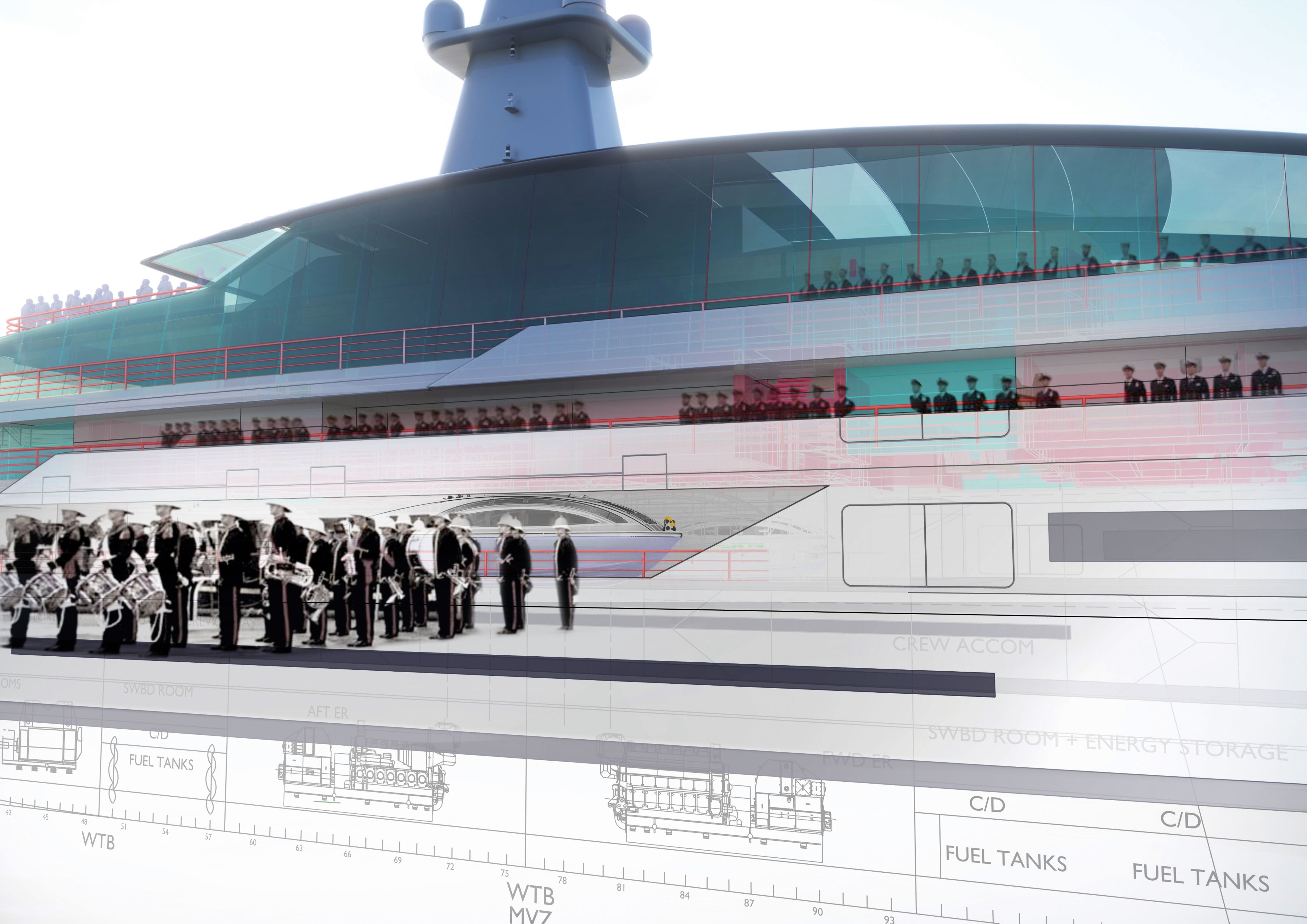

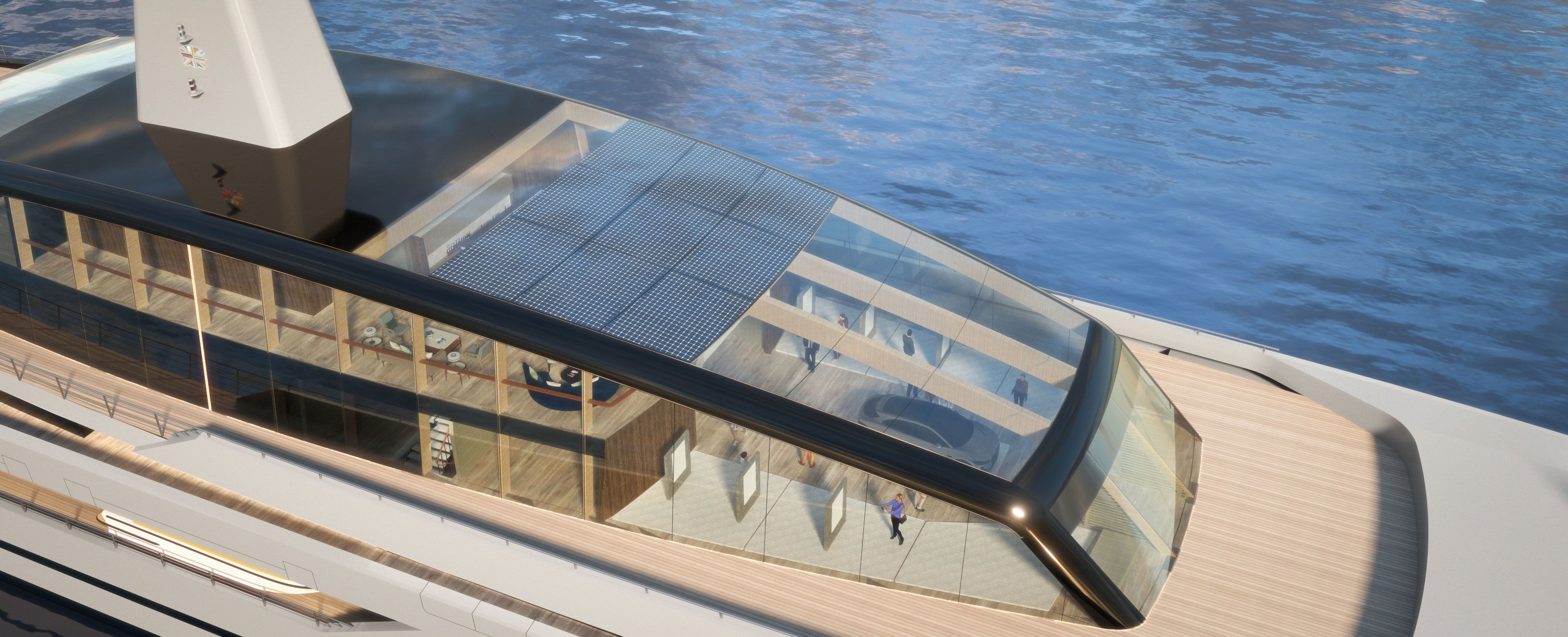

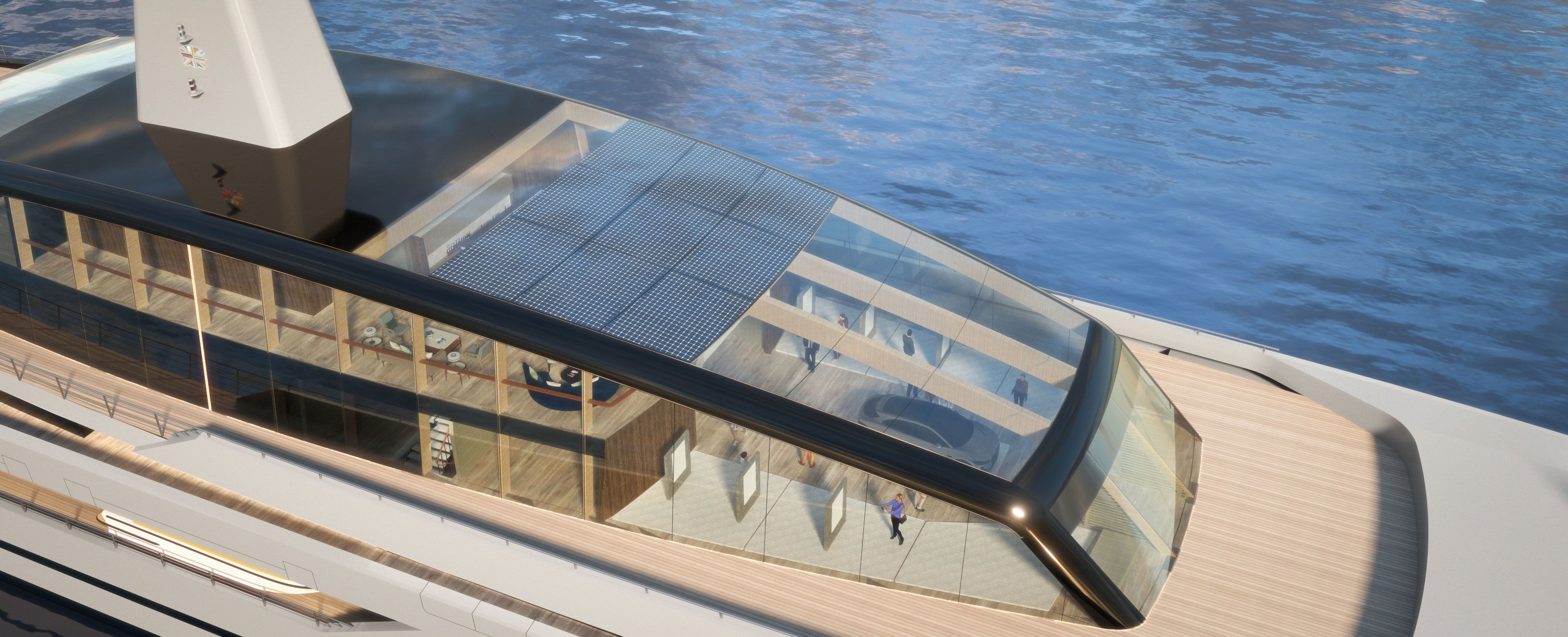

What first grabs the attention is the fully glazed domed superstructure and the panoramic circular lounge under the helipad aft. Respectively, these host the Great Exhibition Room, which is a double-height space with a bar cantilevered above it, and the Lighthouse, a visitor centre that serves as a secondary exhibition space.

London-headquartered structural specialist Eckersley O’Callaghan, which has been responsible for the engineering of transparent Apple Stores worldwide and the groundbreaking glass superstructure on the Feadship Venus, ensured that the impressive glazing of both spaces was doable.

B&R

B&R

B&R

B&R

B&R

B&R

Glass plays a key role in the design, with a double-height exhibition space forward (top left) and a glazed circular visitor’s centre under the helipad aft (top right and bottom)

There is also the Britannia Room forward and two diplomatic areas aft dubbed the Summit Room and the Union Room. Each of these spaces can transform with nearly endless layout configurations for hosting different kinds of functions, possibly even simultaneously.

“One of the complexities of the project was the number of permutations and therefore the required flexibility as a sort of public building,” says Rowell. “At different times, and occasionally at the same time, it is an embassy, a conference centre, an expo centre, a humanitarian support vessel, and it had some defence criteria. Once you start weaving those requirements into scenarios it [becomes] a very sophisticated design project.”

B&R

B&R

"At different times, and occasionally at the same time, it is an embassy, a conference centre, an expo centre, a humanitarian support vessel, and it had some defence criteria."

The well-regarded superyacht design firm teamed up with Houlder and Frazer-Nash, which both have extensive experience working with the Ministry of Defence. The pairing paid off as Team Signal was among the final two contestants, along with Team Harland & Wolff.

What first grabs the attention is the fully glazed domed superstructure and the panoramic circular lounge under the helipad aft. Respectively, these host the Great Exhibition Room, which is a double-height space with a bar cantilevered above it, and the Lighthouse, a visitor centre that serves as a secondary exhibition space.

“The more we worked on it, the more mileage we felt it had, the more interesting the brief became,” says Simon Harris, COO of Houlder, which is best known to the public for its work on the RRS Sir David Attenborough.

While the practical challenges were complex, Rowell points out that the aesthetic goals were less tangible. “You can score your points and work out this very complicated sort of 3D chess of a vessel, but then it has to touch people, and it has to have resonance,” he says.

They took a “best of British” approach to the interiors, encompassing both the materials and the country’s artisans and craftspeople. The decor concept revolved around locally sourced noble finishes – woods such as British walnut and British oak, stones like Cumbrian limestone and Gwynedd slate and fabrics including Irish linen and Scottish tweed. They also found a Welsh company that makes finishes out of plastics recovered from the ocean.

“What was interesting was the combination of that kind of sustainability with a stone carver who is almost a British national treasure himself, who’s done things for Westminster Abbey, the D-Day Memorial, the Bomber Command Memorial… We would have him involved too, which shows the depth of British design heritage and stateliness and the solidity of the boat,” says Bannenberg.

Team Signal looked beyond the royal yacht/cruise ship aesthetic to draw the flagship of the future

Also falling under the sustainability umbrella, along with ingenuity, is how the team future-proofed the vessel. “We wanted to make sure that when selecting machinery, from the fuel type to the overall layout, that we weren’t closing any doors, or as few doors as necessary, to future technology,” says Harris. Their project incorporated a facility to carry future fuels, and Harris says they were looking at space on the upper decks for a kite, rotors or sails.

In addition, they included a laboratory and technology demonstrator facility to showcase and try out emerging green technology. In conjunction with the Lighthouse visitor’s centre, it would be accessible to school groups, who could learn about the inner workings of the vessel and the pathways to sustainable shipping. Providing this type of educational platform was part of the team’s overarching goal to also use the ship to further STEM education and make it accessible to all.

“We thought there was a great opportunity to use the project very positively in that area,” Harris says. “It would be more than just a ship.”

HARLAND & WOLFF

HARLAND & WOLFF

DAVID CORDNER - HARLAND AND WOLFF

DAVID CORDNER - HARLAND AND WOLFF

John Wood of Harland & Wolff. His team began by drawing a GA that would meet all the space requirements, then packaged it in a modern exterior with visual cues linking it to Britannia, like the hull colour, raked bow and three flag masts

TEAM HARLAND & WOLFF

CORE MEMBERS

Team leader Harland & Wolff

Consultant Stephen Payne

Naval architecture/technical oversight Foreship

Interior design SMC Design

Exterior design Clifford Denn Design

SPECS

LOA 153m

Gross tonnage 15,000GT

Harland & Wolff was out to win. The Belfast shipyard that built the Titanic is also one of the few yards in the UK today able to handle the complexities of defence projects. It filled out its team with passenger ship experts such as London interior design firm SMC Design and Stephen Payne, a naval architect formerly with Carnival Corporation who took the Queen Mary 2 from first lines to delivery.

“We knew the team we brought together was the only team with experience in all the sectors that could put something together with shipyard input all the way through the design, to make sure that it was designed in such a way that it could be built on schedule. Because the schedule was very [tight],” says John Wood (pictured left), CEO of Harland & Wolff.

“From the outset, we strove to provide a platform that would give us the maximum number of points,” adds Payne.

Versatility is one of the key interior accomplishments, as the specification required “huge amounts of ingenuity and dexterity to achieve each point”, says Andrew Brown, director of SMC Design. A shining example of this is the convertible exhibition/conference centre. “We needed an exhibition space that could feature the UK’s greatest companies and products as an impressive showcase venue,” Brown says.

“So we built into the ceiling a type of magrodome [sliding-glass roof] that allowed us to lower in special features, whether that be a showcase from Aston Martin or BAE Systems, [in order to] facilitate large exhibitions. This same space could then be transformed to form a conference and seminar space, via tiered and retractable seating levels built into the bulkhead, which, in an automated process, unfolds itself.”

The feel of the interiors is naturally British, but a “diverse, multicultural and enigmatic” British, says Brown. “We took hand-spun fabrics, from small community-led mills in the Hebrides, to furnish the premium suites. We had artworks created by London-based creators using recycled materials captured from the River Thames. When you walk the vessel, you encounter a multitude of carefully curated details each with their own story, giving these macro insights into every corner of the UK.”

Clifford Denn packaged up the interior spaces within an exterior design that he describes as “next-generation Britannia”. “A classic raked bow with an elegant sheer line and blue hull were key to the look,” he says.

It’s a modern design that also embraces heritage elements such as a tiered superstructure and three flag masts. The side-by-side funnels were carefully considered and hark back to the Harland & Wolff ship Canberra, a vessel that Denn says he’s always loved and one that is meaningful to the shipyard’s CEO personally, as Wood first went to sea as a marine engineer on the great ocean liner. “Primarily we wanted a timeless vessel suitable for heads of state, presidents and prime ministers, and not just a large superyacht,” says Denn.

“Primarily we wanted a timeless vessel suitable for heads of state, presidents and prime ministers, and not just a large superyacht,”

As part of the maximising-points strategy, the team decided to accommodate the Royal Navy’s largest helicopter, the 38-passenger AW101 Merlin. Denn managed to integrate the helipad into the hull form rather than bolting it on. However, this left the design with a very long aft deck, which Denn disguised and visually shortened by adding glass windbreaks.

A diesel-electric hybrid system with pods was chosen for the fuel efficiency, but this vessel would also have a green system that had never been done before, Payne says. It occurred to him that it really wouldn’t look good for the ship to be manoeuvring in port with the press looking on and the diesel engines emitting smoke, since this is the most inefficient way to use the engines.

“We hit upon the concept of having another system on board with fuel cells run from methanol, and a battery bank. The idea was that we would charge the batteries from the electric system on board, with the methanol fuel cells giving us enough power to berth the ship,” says Payne. The system would be used mainly for in-port manoeuvring, but if methanol were available locally, the ship could remain green methanol-powered the whole time it was alongside, with the waste product being basically steam and carbon dioxide, which is recycled back into methanol.

Payne was also keen to use a self-deploying, self-stowing kite, which can save significant fuel, and photovoltaic glass on the double-height slanted aft window in the reception room, which would generate electricity.

“I think there will be a time in the future when this comes back, either in a government sense or from a private sense.”

He is still working on behalf of the project, looking at the viability of building and operating the ship on a commercial basis, which would be at zero cost to the taxpayer.

“We’ve got several people interested in bringing in private investment to get the project moving forward,” says Wood. “I think there will be a time in the future when this comes back, either in a government sense or from a private sense.”

GEOFF PUGH - SHUTTERSTOCK

GEOFF PUGH - SHUTTERSTOCK

Ian Maiden

TEAM NEW FLAGSHIP COMPANY

CORE MEMBERS

Team leader/design lead Ian Maiden

Project director Nick Roe

Design Mark Whiteley and ThirtyC

Naval architecture/marine engineering Leadship

Security PDP Marine

Consultant Commodore Anthony Morrow CVO

SPECS

LOA 140m

Gross tonnage 11,750GT

The genesis of the New Flagship Company’s bid goes back a quarter of a century when Ian Maiden first registered the company. Since then, he has been single-minded in his determination to bring a national flagship to fruition, with intermittent success over the years securing parliamentary and press representations. “I’ve had a bee in my bonnet about it for 20-odd years,” he says.

So when Boris Johnson announced the programme in late May 2021, Maiden was more than ready to enter the competition. Taking the design lead for Team New Flagship Company, he secured the services of project director Nick Roe, Mark Whiteley of the eponymous superyacht design firm and Alastair Fletcher of ThirtyC to evolve Jon Bannenberg’s original concept to meet the intricate demands of the MoD’s brief. Maiden spent his own money funding their bid, outlaying £420,000 of “his children’s inheritance”.

Their project carries on with Bannenberg’s long and low lines, but the styling is updated with the larger windows that are expected on vessels nowadays. What the team has managed to achieve with the restrained lines is the Holy Grail of timelessness, with the goal of the design both inside and out being “an eye to the future and a nod to the past”, says Whiteley.

The goal of the design [was] "an eye to the future and a nod to the past"

Impressive but not ostentatious, and elegant with a low silhouette – this was the philosophy behind the design

Maiden was careful to avoid overly superyacht-like design elements that would fuel the detractors’ claims of a vanity project. He won an argument with Jon Bannenberg over the stern, opting for a Constanzi classic cruiser stern with a flat transom below the waterline to accommodate the diesel-electric propulsion pods, instead of the straight transom stern commonly seen on yachts that Bannenberg preferred. In addition, adds Maiden, “We have resisted the easy option of establishing several upper decks, for which superyachts have an indulgent reputation. Fewer decks permit enhanced headroom and increased natural light.”

The hull colour is proposed in two options of blue, a dark one imparting seriousness, and a warmer “friendlier” one, both with the Union Flag insignia on the port and starboard quarters. Three masts are also key to the design. “The MoD brief made no specific mention of royal engagement on board. I nevertheless visualised that on occasions royal participation was likely and three masts would be required at that time: a foremast and, importantly, a mainmast to wear the Royal Standard when appropriate, and a mizzenmast, which in our concept pivots to allow a helicopter to land,” Maiden says.

Whiteley and Fletcher started from scratch when it came to the general arrangement. As visitors cross the threshold, they would be greeted by a large-format art installation, “a bold statement piece to tell the story of the UK’s diversity”, explains the team’s presentation. For security reasons, the public spaces are grouped furthest aft in the GA, with the exhibition and conference areas being the most accessible, surrounded by open deck space that “provides a panoramic view and the great feeling of being on a ship”. The breakout areas and meeting rooms are a deck above, laid out for maximum social engagement with a welcoming and light decor.

“Britishness” is a theme throughout the interior. For example, in the observation lounge is a Union Jack bar, which Maiden describes as “a room with a warm and friendly atmosphere… that unashamedly flags up British achievements that led the world at the time and that benefit the world today. The first Covid-19 vaccine, the World Wide Web, radar and the jet engine spring to mind.”

Gary Bird, managing director of security firm PDP Marine, points out that the vessel, as a floating embassy, had to be both hospitable and intensely secure – inherently opposite goals. “The vessel was to welcome a broad spectrum of guests and visitors, while also serving as a platform for statecraft and diplomacy at the highest level.

It was to be a tool for cultural exchange, but it was imperative that it embraced counter-intelligence capabilities commensurate with such a conspicuous global diplomatic facility. Further, it had to be able to protect itself, responding to threats through proportionate escalation and, if necessary, over-match attempts at violent seaborne assault. Quite a task for a yacht, but one I’m proud the consortium delivered,” he says.

The end of the competition does not mean an end to Maiden’s support for such a vessel, and he is now seeking private investors to fund the build. “I can’t see a political downside if it’s paid for by the private sector,” he says.

BRIAND The blue and white ribbon can exhibit messages via thousands of LED tiles.

BRIAND The blue and white ribbon can exhibit messages via thousands of LED tiles.

Philippe Briand

Philippe Briand

TEAM FESTIVAL

CORE MEMBERS

Builder OCEA(UK)

Naval architecture/engineering/exterior

design/space planning Vitruvius Yachts

Interior design Zaha Hadid Architects

Lighting specialist Jason Bruges Studio

SPECS

LOA 125m

Gross tonnage 7,500GT

The capital A in Team FestivAl gives the first hint of this bid’s defining difference. It references the element symbol Al, for aluminium. The team was led by OCEA(UK), a subsidiary of OCEA Group, which designs and builds exclusively in the material that’s 40 per cent lighter than steel.

“Most of my career I’ve seen a brown smog over the horizon caused by the effluent from ships’ funnels; it’s a dirty industry and it needs to be cleaned up. And aluminium, I’m convinced, is the metal to help us on the way, because it gives you the weight margins to put in low and zero-carbon technologies,” says OCEA(UK) CEO Ken Houlberg.

Theirs was to be a project that would involve and invigorate the nation. Houlberg even envisioned a Blue Peter appeal where the country would be encouraged to collect cans that would be turned into the ship, as OCEA builds vessels out of 70 per cent recycled aluminium.

"It didn’t matter how small a gain, if you make the cumulative sum of the gains you end up with something amazing"

To reduce carbon emissions, they adopted the “incremental gains” approach of Sir David Brailsford, the coach who led the Great Britain Cycling Team to many victories with a philosophy that boils down to every little bit helps. “It didn’t matter how small a gain, if you make the cumulative sum of the gains you end up with something amazing,” Houlberg says.

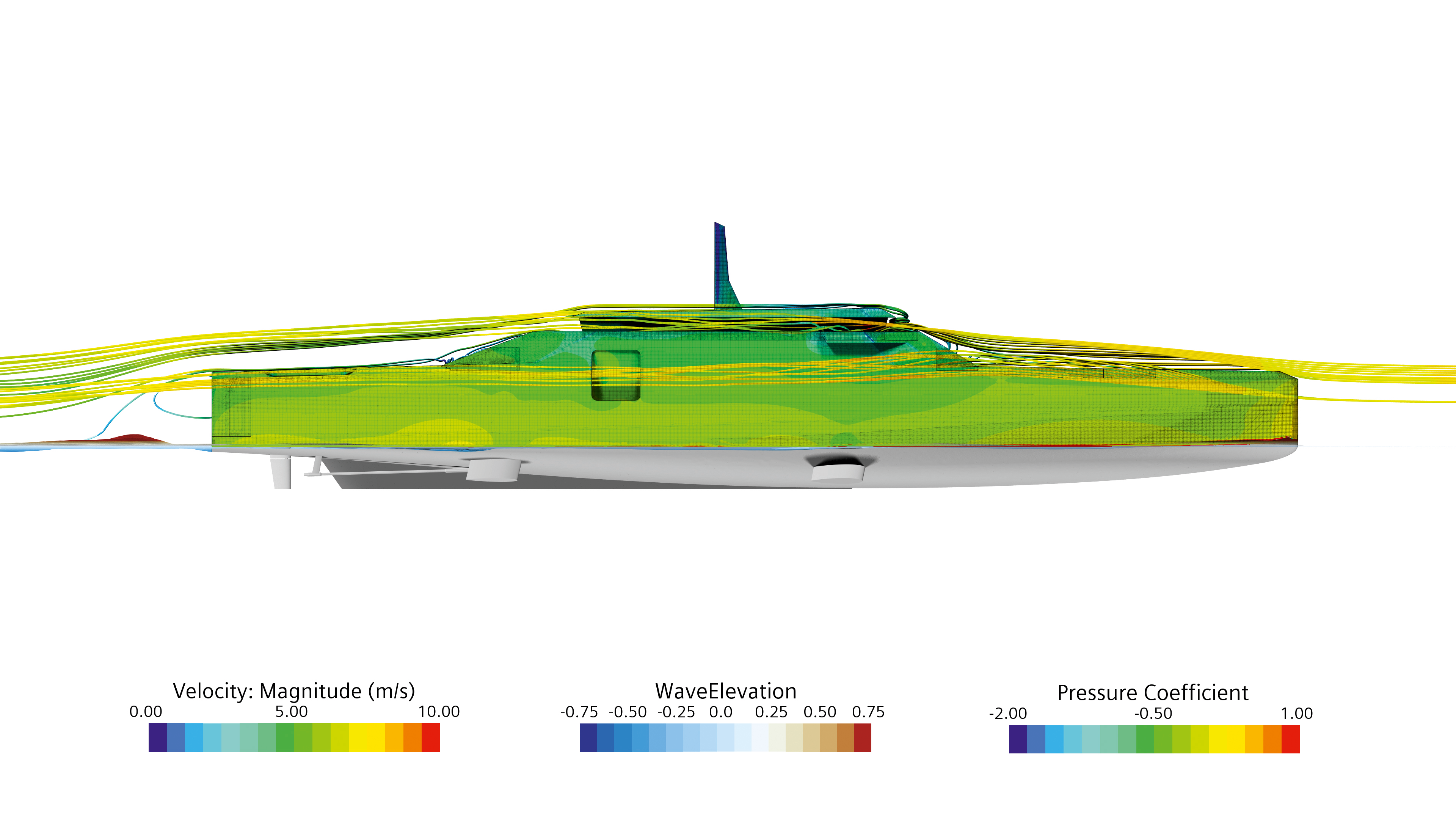

For naval architecture, OCEA turned to Philippe Briand in London, who helped pioneer the concept of an efficient motor yacht back in 2008 with his Vitruvius Yachts brand. Briand started with a hydrodynamic hull form and opted for four compact propulsion pods to keep it clean underneath. “A ship that’s hydrodynamically as efficient as possible may see 10 to 12 per cent gains, or lowering of CO2 emissions,” Houlberg says. “Then you also look at the aerodynamic efficiencies, an approach that is unusual for ships, but which can offer another four to five per cent reductions in CO2.” Briand used CFD testing to check the windage and drew a streamlined, aerodynamically optimised superstructure. Adding to those gains were hydrogen fuel cells, solar panels, heat extraction and even efficient pipework, each incrementally lowering the vessel’s CO2 emissions and allowing it to run with zero emissions for short-range manoeuvring in territorial waters.

BRIAND

BRIAND

At 125 metres, this submission is the most petite among its peers, and for a good reason, Briand explains. By capping the volume at 7,500GT and drawing a longer length than would be expected for that gross tonnage, he got the most efficiency out of the hull. “The longer the boat, the less resistance in the water,” he says.

In addition, the size meant the ship would have come in under-budget. “Our naval architect job was to design [the MoD requirements into] the most compact possible boat, so the overall cost to the taxpayer would be optimised,” Briand says.

To meet the MoD’s massive brief at that volume, the project relied on spaces being ultra-flexible. Grouped aft are exhibition centres, conference rooms and dining spaces that could interchange their functions. A Mission Bay aft on the lower deck is unique among the bids. The vast, open space could transport goods and even host medical facilities for humanitarian missions, or perhaps modular labs for scientific research, or it could be the venue for concerts for the public or informal trade shows. Another engaging space is found just forward, a longitudinal passageway that allows visitors to peek into the engine room.

BRIAND

BRIAND

A USP of the design is the LED ribbon that wraps around the superstructure. Seen from above it takes the shape of the Union Flag; it was a subtle way to bring in the emblematic reference. With 3,082 LED tiles, the ribbon is also a ticker tape, able to send out messages in host ports in any language.

This was the work of the innovative Jason Bruges Studio in London, which also envisioned an interactive LED bulkhead panel that rises through three stories of the ship’s central glazed atrium, reacting as visitors pass by.

While the exterior styling is thoroughly modern, Briand played with the connection to Britannia with the hull colour and a gold cove stripe, and by recreating the ambiance of the royal yacht’s balcony with a wooden guardrail.

"Every single person who would walk across the brow... would leave that ship with a positive experience of having been on board"

For the yacht’s interior design, OCEA partnered with Zaha Hadid Architects, a London firm with global influence. “They could bring another aspect to this project in terms of branding and the sort of lived experience,” Houlberg says. “This is about every single person who would walk across the brow, how they would leave that ship with a positive experience of having been on board. Whether they were members of the crew, members of the public, VIPs or heads of state, they all had to have a positive experience. And Zaha are specialists in providing architectural solutions that did that.”

Houlberg says he felt the project could have led UK shipbuilding into the modern era. While it did not go forward, the technological advances the team made will. “It’s only when you bring together a consortium of businesses like we did that you begin to realise how powerful and complementary the technologies are. They are already benefiting many of our other projects. We’ve designed what I think is the world’s first zero-carbon 90-metre SOV (service operation vessel) for the offshore renewables industry.”

THE CASE FOR SAIL

Superyacht designer Steve Gresham was ready to go when the competition was announced. He had already drawn up a flagship concept in 2020 as a PR exercise. His 118-metre Britannia had something none of the other bids would offer – sails.

It would recall the days of the Royal Navy during the Age of Sail, but enjoy the tech of today with a modern, fully automated rig. Then Gresham learned the scope of the MoD process and decided not to continue with the competition.

“I still stand by it though,” he says. “I still think the national flagship should be a sailing boat. There are enough big private vessels with sails out there to justify the principles and the concept of a large sailing boat.”

Gresham acknowledges that any sailing ship today has to have an engine; his would have diesel-electric propulsion. “But you could choose to supplement engine use with wind power to save fuel and make it as environmentally conscious as possible.”

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE NATIONAL FLAGSHIP

DECEMBER 1997

APRIL 1998

1999

2005 to 2010

31 JANUARY 2020

30 MAY 2021

28 JULY 2021

MID-AUGUST 2021

EARLY OCTOBER 2021

MID-OCTOBER 2021

LATE DECEMBER 2021

MID-JANUARY 2022

LATE MARCH 2022

22 APRIL 2022

LATE MAY 2022

7 JULY 2022

6 SEPTEMBER 2022

23 SEPTEMBER 2022

24 OCTOBER 2022

7 NOVEMBER 2022

2024 to 2025