INTO THE

DEEP

After thousands of successful submarine trips in recent years, the yachting world was rocked in 2023 by news of the Titan disaster. Tom Ough explores how it has affected the personal sub industry, and examines the continued appeal of diving deeper

Patrick Lahey has spent much of his life building and advocating for submersibles. But when he learned that a dear friend planned to visit the wreck of RMS Titanic in a craft suspected to be dangerous, he was horrified. “We had many conversations about it,” Lahey recalls, a year on, “and I couldn’t have been more vocal about it.”

The friend was Paul-Henri Nargeolet, a Frenchman who had been part of dozens of previous expeditions to the famous shipwreck. Over the years, Nargeolet had worked with the French Research Institute for the Exploitation of the Sea to assist with the recovery of more than 6,000 artefacts, from a section of hull to a leather bag containing sheet music and love letters.

Despite Lahey’s warnings, the 77-year-old was seduced by the idea of one more trip to the wreck that had led to him being nicknamed “Mr Titanic”. “It was appealing enough,” Lahey says glumly, “that he was willing to put aside any concerns he had about his own safety, I guess. I don’t know. I’ll never know. And it’ll trouble me, I’m sure, for the rest of my days.”

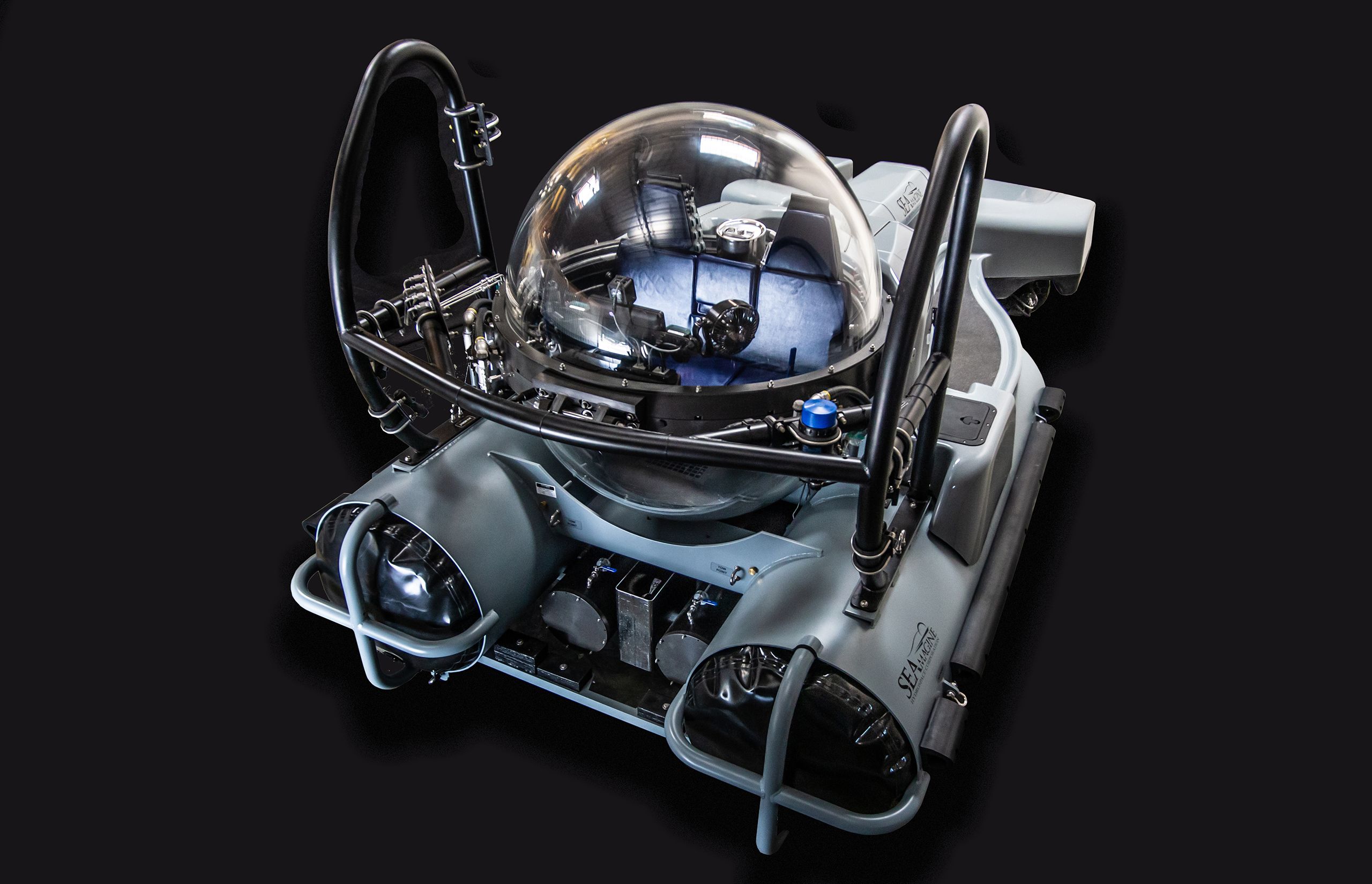

ROLDOLPHE HOLLER The SEAmagine Aurora-80 can dive to depths of 1,000 metres.

ROLDOLPHE HOLLER The SEAmagine Aurora-80 can dive to depths of 1,000 metres.

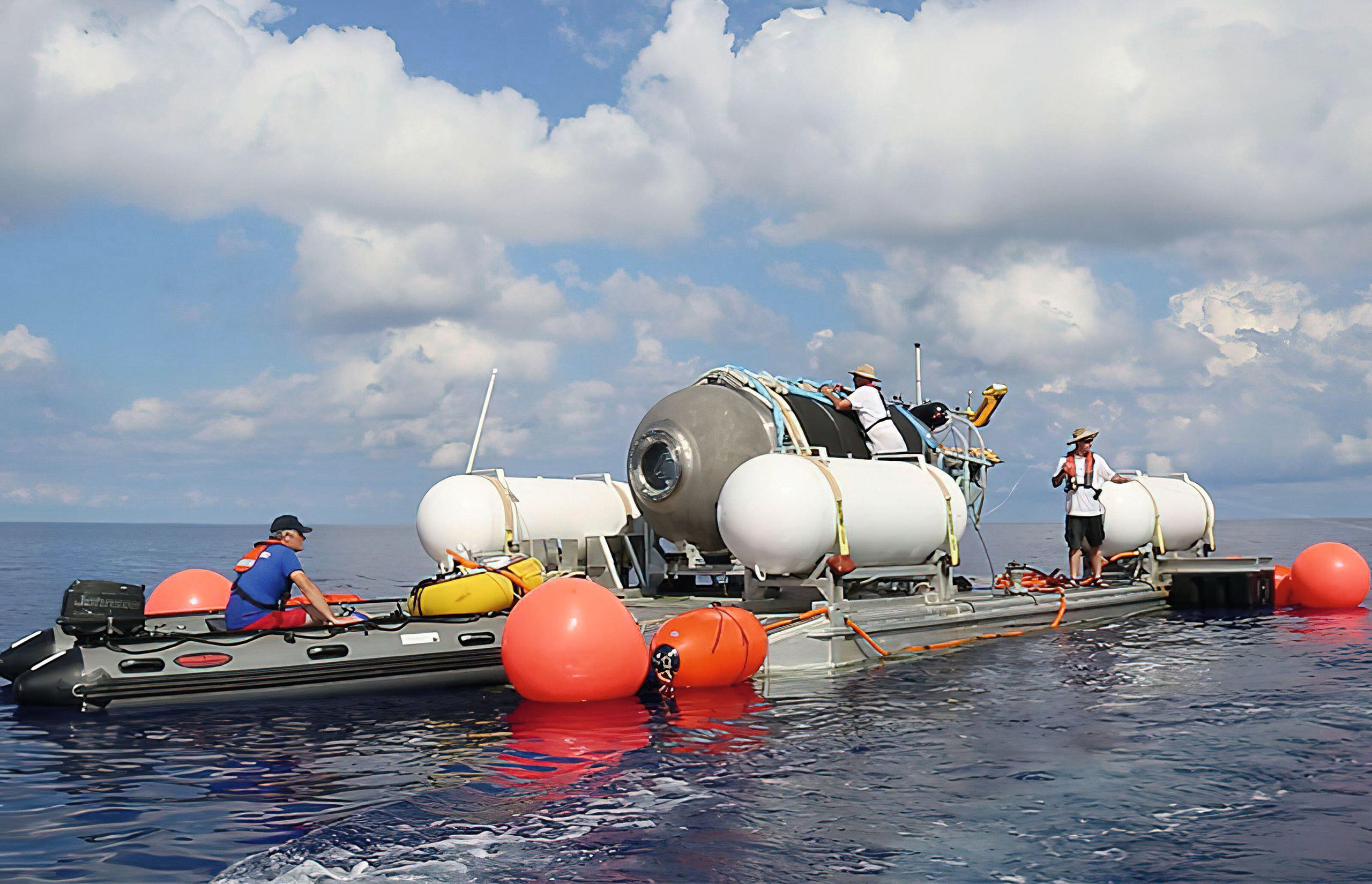

On 18 June 2023, Titan set off on its first expedition of the year. It was manufactured by the company OceanGate, whose CEO, Stockton Rush, was on board with Nargeolet and three tourists: the British businessman Hamish Harding, the Pakistani-British entrepreneur Shahzada Dawood and his son, Suleman. One hour and 45 minutes into its mission, the submersible’s mothership, Polar Prince, lost contact with the craft and its crew.

Lahey first learned that something had gone wrong with Titan when he was on vacation in Sardinia. “My phone blew up, my computer blew up... Naturally, I was very concerned.”

For four days the world waited. Titan had 96 hours’ worth of oxygen aboard. Could its five passengers be alive, stranded at the bottom of the ocean? The discovery of debris, however, confirmed what observers feared and what experts privately believed to be the overwhelmingly likely outcome. Before reaching the shipwreck, Titan had imploded under water pressure equivalent to the weight of the Eiffel Tower, resulting in the instantaneous deaths of all five people aboard.

The four days of ambiguity gave the disaster, as it turned out to be, an unseemly virality. Titan, briefly, became the focus of worldwide fixation. When worry turned to horror, the globe’s attention swung towards OceanGate’s Rush and his gung-ho approach, eschewing safety certification in the name of fast innovation.

Rather than relying solely on titanium, one of the strongest metals on earth and the material of choice for other deep-dive submersibles, OceanGate had built its hull out of carbon-fibre reinforced plastic, which is lighter but weaker. Instead of bespoke mechanical controls, Titan used a $30 wireless games controller.

Rush employed recent graduates rather than experienced engineers for some elements of the build. Titan expeditions were frequently affected by minor problems. In a lawsuit filed in 2018, OceanGate’s director of marine operations, David Lochridge, alleged that he was fired after refusing to authorise manned tests of Titan until the company paid for the hull to be scanned. He had presented Rush with a 10-page report documenting his concerns over safety and objecting to OceanGate’s “deviation from an original plan” to conduct non-destructive testing on the hull.

NICK VEROLA: TRITON SUBMARINES

NICK VEROLA: TRITON SUBMARINES

EYEPRESS NEWS - SHUTTERSTOCK

EYEPRESS NEWS - SHUTTERSTOCK

AMERICAN PHOTO ARCHIVE: ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

AMERICAN PHOTO ARCHIVE: ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

AMERICAN PHOTO ARCHIVE: ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

AMERICAN PHOTO ARCHIVE: ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Top left: Patrick Lahey of Triton Submarines called on OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush (top right) to slow down his “experimental approach”. Titan was built out of carbon-fibre composite, instead of titanium like other submersibles. Bottom right: Inside Titan on an expedition before its ill-fated outing

Lahey, who is CEO of the submersibles manufacturer Triton, was one of many to call on Rush to slow down. In a letter written by leaders in the submersible industry in 2018, and co-signed by Lahey, Rush was warned that he was putting lives at risk. OceanGate’s “current ‘experimental’ approach”, the industry colleagues wrote, could result in negative outcomes “from minor to catastrophic”.

The tragedy now dogs the submersibles industry. The order books remain full, but questions naturally abound. When we speak, Lahey has just returned from the Fort Lauderdale International Boat Show, where Titan was on everyone’s lips. “You could bet that within a few minutes of any conversation we had about the subs, the issue of safety came up.” Given the amount of regulation that governs watercraft, how could the tragedy have happened?

Titanic lies in international waters, where the law of the land is limited. While ships operate under the jurisdiction of the country whose flag they carry, and are therefore bound to national standards of safety, submersibles are not ships, and are less straightforward to police.

The US Coast Guard provides guidance for certification of submersibles; the International Maritime Organization offers guidelines for their design, construction and operation, in addition to more general rules about safety, which are enforced by member states. Had Rush survived, though, it is not obvious whom he would have been hauled up in front of.

Whether Rush broke these rules will be established by an inquiry, but he certainly broke convention. OceanGate was unique in that it offered wealthy passengers the chance to visit the world’s most famous wreck, Titanic, 3.8 kilometres below the surface.

What started out as the scientific endeavour of scanning the wreck had evolved into a tourism venture, with OceanGate inviting a handful of what it euphemistically termed “mission specialists” –whose main qualifications were being able to afford the $250,000 (£196,000) trip – along for the rides in 2021 and 2022.

And as Lahey and his peers point out, pretty much every submersibles manufacturer abides by a strict process of third-party certification. Triton and other companies, such as U-Boat Worx, submit their materials, designs, components and finished craft to testing and rating by independent accreditors such as the American Bureau of Shipping. Rush felt that certification was holding back progress, and refused to seek it. “I think I can do this just as safely by breaking the rules,” he told an interviewer in 2022.

“I think the industry could use a more uniform set of operational standards everyone can agree upon”

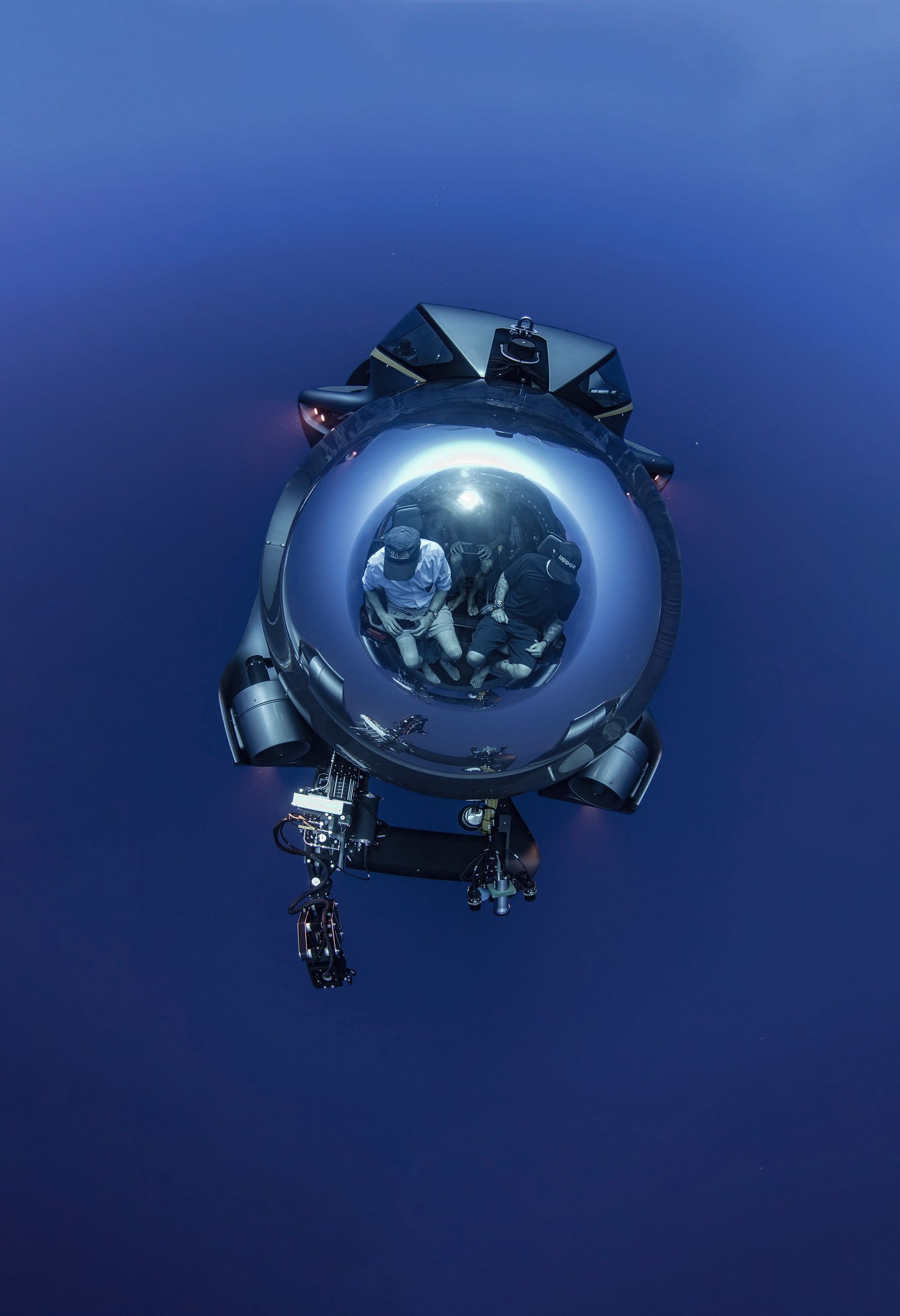

Lahey describes the accreditation as arduous but necessary. “I can’t just run out to Home Depot and grab a part and throw it in the submarine,” he says. Take a Triton 3300/3, a model that can reach a depth of 1,000 metres and which is often used for undersea filming. A pilot and two passengers sit in a transparent, domed hull, with machinery housed in surrounding casing.

The three armchairs are made of flame-retardant material; the cabling and wiring have to be able to self-extinguish, in the case of fire, without creating noxious fumes. The innovation of the transparent domed hull, made of 90mm thick ultra-tough acrylic, was the result of years of testing. The machinery is housed in a shell made from titanium, which surrounds the dome on either side and behind it.

Triton submersibles are tested at pressures at least 1.2 times that of their advertised maximum operating depth. As the team likes to joke: “When the paperwork weighs as much as the submarine, you know you’re done.”

Charles Kohnen, president of the submersibles manufacturer SEAmagine and another signatory of the letter to Stockton Rush, says that he doesn’t believe more regulation is needed for submersible construction. “The code of rules for fabrication works well,” he said, referring to the third-party classification processes.

He added, though, that there could be more international uniformity on submersibles’ “operational protocol or standards”: what people use submersibles for, and where, and how. “There are a number of published operational guidelines for manned subs that have served well, but the various operators use the protocols that the sub manufacturing company teaches them and there are variations. I think the industry could use a more uniform set of operational standards everyone can agree on.”

AMERICAN PHOTO ARCHIVE - ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

AMERICAN PHOTO ARCHIVE - ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

“In your race to Titanic you are mirroring that famous catch cry: ‘She is unsinkable’”

Of Titan, he said that the craft’s “fabrication and operation did not meet any standards and did not follow any of the standard protocols that have served the industry well for many decades.”

The US Coast Guard has partnered with other bodies to conduct an inquiry into the Titan tragedy. It is due to be published within a year of the incident, mid-June this year. Will the industry be regulated?

The Marine Technology Society, an industry group, has recommended that SOLAS, the international maritime treaty that sets safety standards for merchant ships, be amended to treat submersibles as ships, requiring even those operating solely in international waters – as Titan did – to be flagged and classified. Insiders expect that the Coast Guard will update its existing requirements for submersibles operating in US waters, even if that wouldn’t directly affect activity in international waters.

MARK THISSEN - NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

MARK THISSEN - NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

There is plainly risk involved in going very deep down, but the vast majority of submersible trips are to much shallower depths. In 1973, two divers died when their submersible became trapped in wreckage off Key West, Florida, but since then there have been hundreds of thousands of submersible trips, perhaps millions, without a single death prior to the Titan tragedy.

To demonstrate how seriously responsible players in this sector take safety, and why thalassophiles with several million dollars to spare ought still to consider sinking them into a submersible, I was invited for a ride in a Triton 3300/3. This 3300/3 in particular is owned by Carl Allen, the plastics entrepreneur turned treasure-salvager who uses it to visit the wreck of Maravillas, a gold-laden Spanish galleon that sank near the Bahamas in 1656.

Allen was away, but had left us Axis, the 55-metre Damen mothership of the 3300/3. It was the end of hurricane season, with clouds streaking across the Bahamian skies, so our captain decided that, for safety reasons, our dip would be only a shallow one. Find yourself in this situation and you will note that the caution with which you arrived might be replaced by frustration at not getting to do anything riskier.

You begin your voyage by dropping into the orb via a manhole-like aperture at the top. Sitting in your armchair within the orb, you’re roughly half submerged, about chest-high in the sea. When the descent begins, the submersible tips back slightly, as if psychologically readying itself.

The waterline falls for a moment, and then, with the machinery chugging away, begins to rise. And because it was a little choppy on the day, the water swirled and splashed against our orb, taking up more and more of our field of vision, much as, when you initiate a washing cycle, water rapidly fills the machine’s round window as it starts to descend.

CHAD BAGWELL: ALLEN EXPEDITIONS

CHAD BAGWELL: ALLEN EXPEDITIONS

And then we were under. We were close to the Bahamian shore, and it was only a few metres to the bottom. Here, things were quiet and clear. Before us lay a seabed of coral. In and out of its gnarly crevices darted blue chromis fish, tiny and iridescent. Watching this scene, I was taken aback by the near-tangible reminder of the sheer amount of life going about its business at any given moment. These lively square metres of ocean floor, multiplied by billions – a quantity of life and lives beyond human comprehension, proceeding unwitnessed and uncounted.

Given the events of last year, I was more zealous than I might have been in establishing the safety of the submersible I was in. Troy Engen, my pilot in the Bahamas, was in constant communication with colleagues on the surface via an underwater telephone that can send audio signals through water. If that stops working then pilots can turn to a text-messaging system as a backup.

If Engen were to lose touch with the surface, he would bring the submersible back up using a routine familiar to the support team. Should we take on water, he’d do the same, using one of four means of returning to the surface, ranging from the use of thrusters to the dropping of weights from the sub via a mechanical hand pump.

Should the submersible’s air supply become compromised, the three of us within it could all reach for scuba gear to breathe. If we were all to fall unconscious, a dead man’s switch would bring the submersible back to the surface. And if we were to become tangled up in a shipwreck, Engen would use the sub’s mechanical arm to cut lines or cables.

A sub is monitored by its mothership at all times via underwater acoustic positioning, so if a terrible combination of the above happened simultaneously – if we all fell unconscious while the sub was tangled up, say – the surface team could dispatch divers if the depth were shallow, or a remotely operated vehicle if we were in deeper waters.

Triton requires its sub users to create a rescue plan for each dive, and the company maintains a round-the-clock hotline in case its vehicles are needed in a rescue operation. As for who the submersible pilots are: a Triton client can send whoever they like to the company’s training programme, which includes piloting, maintenance, fault correction and externally moderated at-sea testing.

Before entering the submersible, passengers are told how to find the scuba breathing gear in case the air supply is compromised, and how to communicate with the support vessel in the event that the pilot is incapacitated. If you are hoping you’ll be able to take aboard a lighter, cigarettes, or anything flammable, you’ll be disappointed. But if the safety briefing has left you confident enough to knock back a glass of fizz, you might be in luck; that’s what some previous passengers did in the sub I tried, leaving a cork I later found.

SHUMLIK-BLUM

SHUMLIK-BLUM

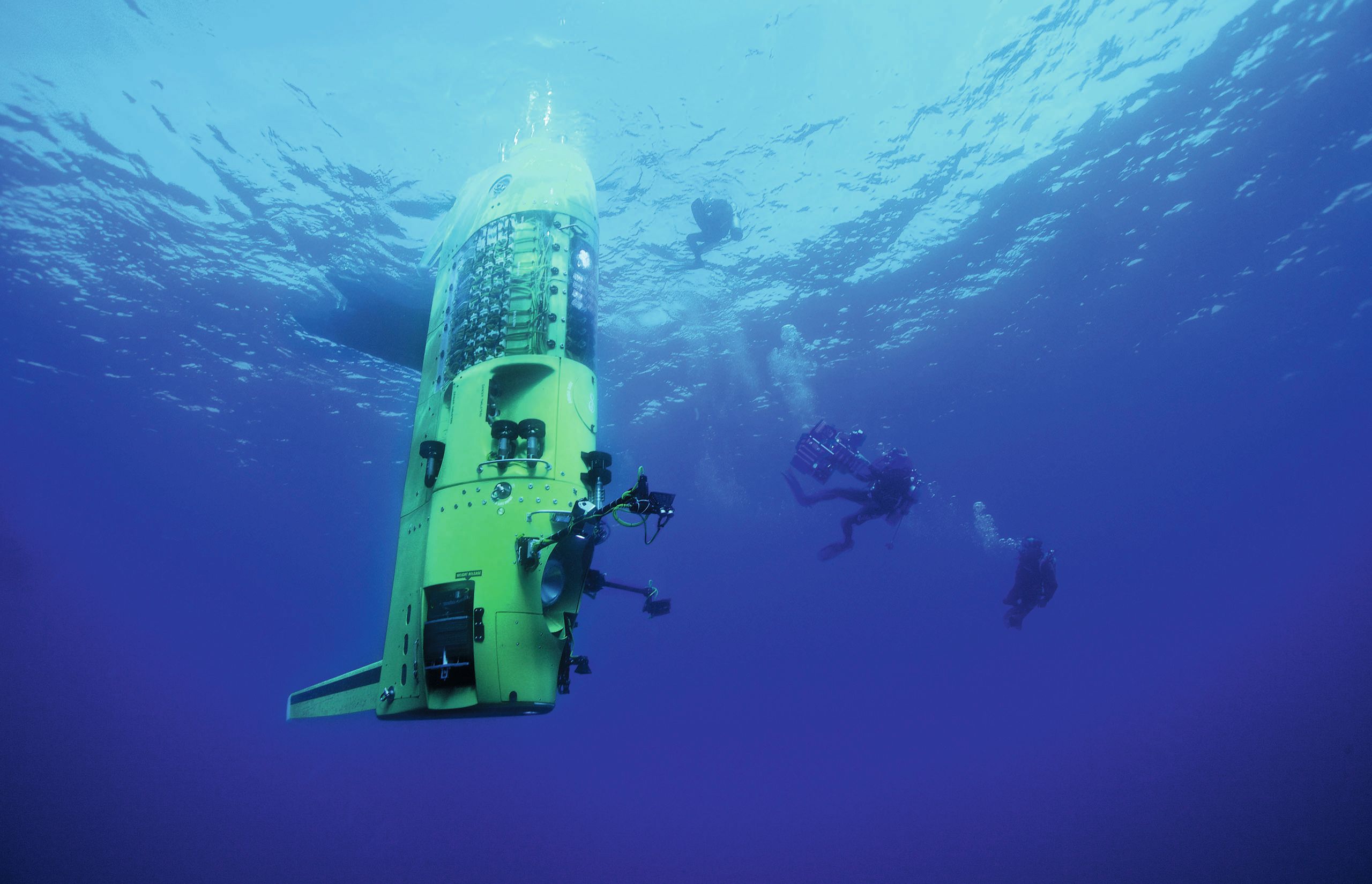

As Rob McCallum can testify, the 3300/3 is an entry-level submersible. Others go much deeper, and probably give a glimpse of the future of the industry. McCallum is the co-founder of EYOS Expeditions, which organises bespoke superyacht trips that often involve leisure submersibles, and he was another industry leader to warn Stockton Rush to raise his safety standards. “I think you are potentially placing yourself and your clients in a dangerous dynamic,” he wrote, three months before the implosion of Titan. “In your race to Titanic you are mirroring that famous catch cry: ‘She is unsinkable.’”

McCallum is one of the few people to have visited Challenger Deep, 11 kilometres beneath the surface of the Pacific. The purpose of this expedition, conducted in 2021, was to test acoustic navigation equipment that support the deep-ocean research of the future. These trips are very different to gentle Bahamian dips. Whereas I entered 3300/3 with bare feet and wearing a t-shirt, those on expeditions to the ocean’s icy depths must wrap up warm.

Nevertheless, the voyages to the ultra-deep sound less fraught than one might imagine. “I always find subs extremely relaxing,” McCallum says, “because once you get below 10ft [three metres], the movement stops and life just slows down. It’s a long commute to the bottom, about four and a half hours.” Don’t assume it’s all wine and roses, though, especially if your Aussie crewmate is in charge of the music. “If you’ve ever considered a new torture device then being in a titanium capsule with Australian country and western music for four hours is right up there.”

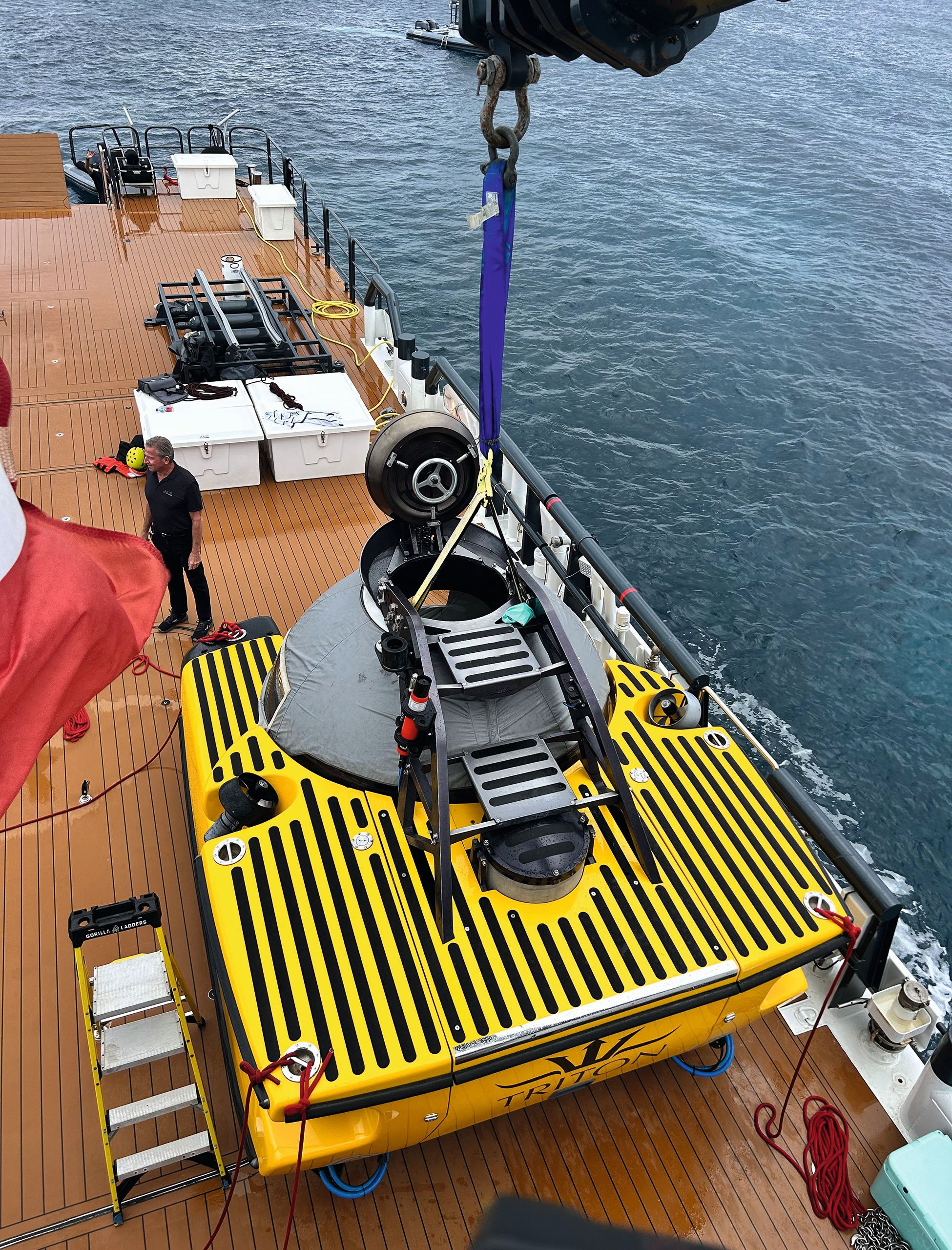

TRITON SUBMARINES EYOS organises yacht expeditions with submersibles

TRITON SUBMARINES EYOS organises yacht expeditions with submersibles

At the bottom, he and his fellow voyager worked quickly to gather footage of the primitive lifeforms that eke out an existence in the pitch darkness and immense pressure. “It was probably the most valuable hour of my life.” But there was time for a moment of levity: the deepest beer in history.

The trips to Challenger Deep are a dramatic illustration of the industry’s rapid evolution. The leading submersible manufacturers were founded in the 1990s and early 2000s; before then, what few submersibles existed were generally in the possession of the military or of institutional science.

Civilian manufacturers have made it possible for billionaires and centi millionaires to get involved, and their custom has helped fund advances in submersible capability. Triton’s first submersible went to 305 metres, but private submersibles now go deeper – much deeper – and do so for longer.

By the count of the Marine Technology Society, the world currently has 161 active submersibles, of which 10 can dive to 4,000 metres or deeper. The global manned submersible market reached a value of $186 million in 2022, rising rapidly since the turn of the millennium. You’ll find submersibles on cruise liners as well as private yachts, and sometimes elsewhere; a 24 person, 100-metre-depth edition was recently shipped to a coastal resort in Vietnam.

As the world of submersibles opens up and exposes new audiences to the wonders of the deep, McCallum believes it could seed a new generation of submersibles of all kinds – both in the scientific and leisure sphere. “If you think about the Model T Ford, at the time, it was like, ‘It’s the pinnacle of engineering – get rid of the horses, get rid of the carts...’ We look back now and we think that was the beginning.”

McCallum’s deepest dives have used Triton’s 36000/2 submersible, whose windows, out of current technical necessity, are much smaller than the massive transparent orb of the submarine in which I had dived in the Bahamas. Future deep diving submersibles, suggests McCallum, could have transparent hulls, they could carry more people and they could have sufficient onboard power to sustain scientific operations such as drilling. “Anything that doesn’t break a law of physics is possible,” he said.

It might not be breaking the laws of physics, but the industry is nevertheless advancing science. Dr Paris Stefanoudis, a marine biologist at the University of Oxford and a veteran of two submersibles missions, told me that being down there in-person has advantages over sending an unmanned vehicle. “For example, the cameras might be looking at a specific part of the bottom of the sea floor, but you might be there observing another fish doing something that it wasn’t supposed to do, or something that wasn’t captured with the cameras.”

Top: The bridge on board Axis; bottom left, a submersible on deck; bottom right, a SEAmagine personal sub

Submersibles are expensive and exclusive, but being there in-person, says Stefanoudis, also tends to leave a deeper impression on people than simply watching footage – hence the occasional invitations extended to policymakers.

The rough theory of change here is that the greater the interest from influential people, the quicker we’ll chip away at our gigantic ignorance of what goes on under the surface. The Nekton Foundation, which had arranged Stefanoudis’ trips, chartered a Triton sub, but philanthropists sometimes facilitate the work of scientists by lending their gear – submersibles and support vessels –and crew.

And even without a scientist on board, a submersible user can contribute to science. It’s harder to argue than it used to be that we know more about the Moon than about the sea floor, but there are still some easy discoveries to be made. “I made a new shark discovery in French Polynesia without even trying,” Kohnen tells me.

In their hour at Challenger Deep, McCallum said he and his fellow diver found two “holy grails” of marine biology. These were sulphur mounds, which are important because they are a source of energy at full ocean depth and microbial matting; and biological ooze containing the simplest form of life, resembling the sea-floor biological communities from which, several billion years ago, complex life probably arose.

Submersibles have also enabled such achievements as the first-ever footage of a live giant squid, Architeuthis dux. It would be most unlike Homo sapiens to see these tantalising glimpses of an alien world and to refuse to explore it further.

First published in the March 2024 issue of BOAT International. Get this magazine sent straight to your door, or subscribe and never miss an issue.