WHATEVER HAPPENED

TO SADDAM HUSSEIN'S

YACHT?

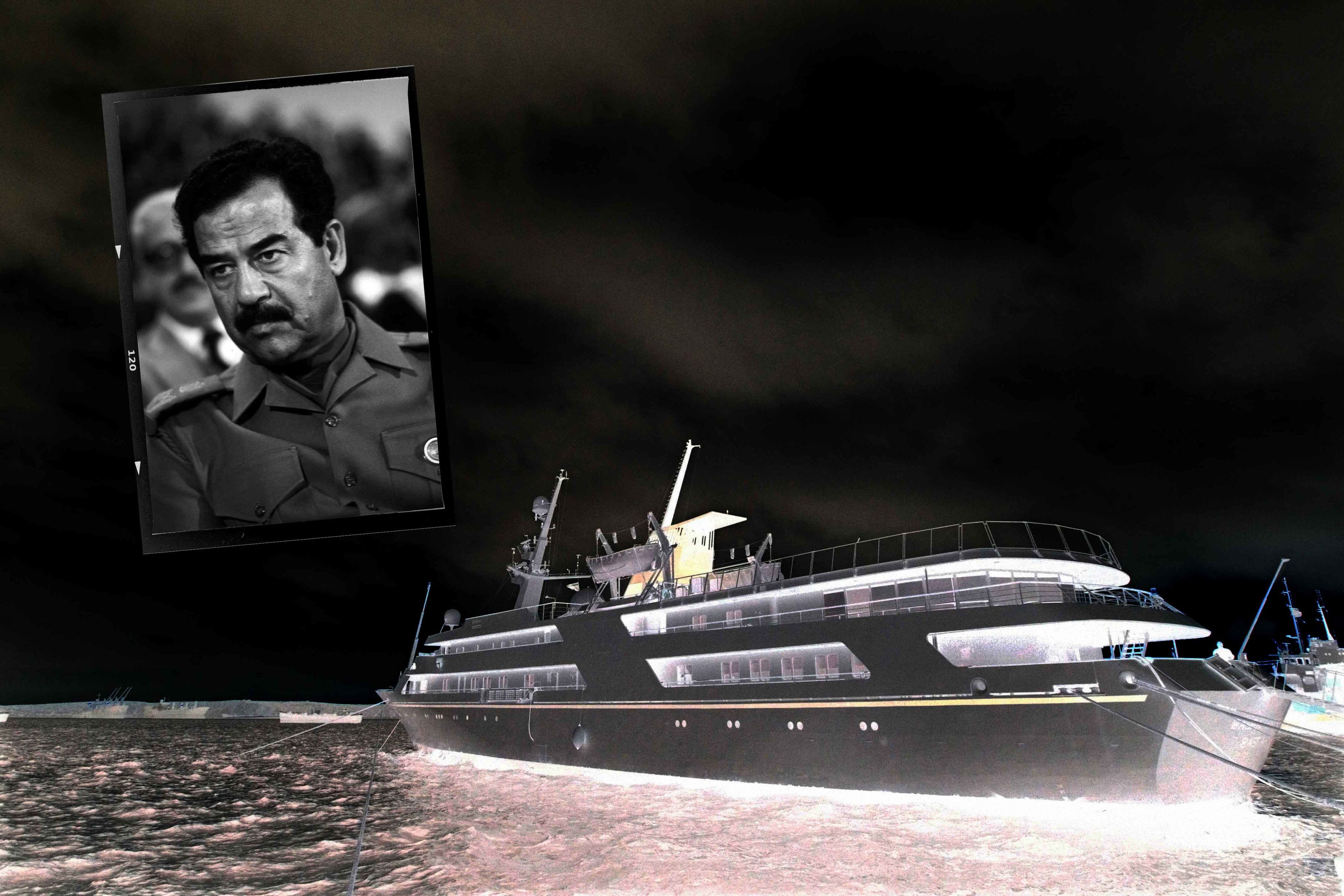

Sam Fortescue investigates the strange history of Saddam Hussein's 82-metre Basrah Breeze

The directors at the struggling Danish Helsingor Vaerft shipyard could hardly believe their eyes when the order from the Iraqi authorities came through.

Just two weeks earlier, the managing director of the shipyard had handed a brochure for his training ships to the Iraqi embassy in Copenhagen. It was written in Arabic and the diplomatic staff had promised to forward it to Baghdad. The order, signed by Iraq’s Ministry of Defence, came back with unprecedented speed: “We want to buy such ship,” it read.

“But it would be naive to think that you could just come and get a ship contract,” Helsingor Vaerft managing director Esmann Olesen would later write in his memoirs. “It took a whole year and many trips to Iraq and also from Baghdad to Elsinore before we could put our signatures on the new contract” for the training ship.

“With its 82 metres, this motor yacht was among the largest of its kind in the world”

Nevertheless, the relationship with Saddam Hussein’s regime in the late 1970s kept the shipyard, based in the port town of Elsinore in eastern Denmark, afloat, and led to five further orders from the Middle Eastern country.

It was not without controversy, though. The next order was for three roll-on/roll-off ferries, but the Iraqi chief of staff was also demanding warships from the Danish yard. “That was completely out of the question for political reasons,” remembers Olesen. “The three Ro-Ro ships we built gave rise to a great deal of speculation and newspaper scandal, because journalists wrote that they could be used for the transport of equipment and troops.”

Then, in 1980, the head of the Iraqi fleet got in touch about adapting a research vessel design to build a presidential yacht. After lengthy negotiations involving visits to Iraq and delegations of tight-lipped admiralty staff from Baghdad, a deal was struck for a “ship of class” which went into the order books as number 423. “With its 82 metres, this motor yacht was among the largest of its kind in the world.”

STEPHANE DANNA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

STEPHANE DANNA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

STEPHANE DANNA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

STEPHANE DANNA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

EPA/SHUTTERSTOCK

EPA/SHUTTERSTOCK

Top: Some time between 2003 and 2006, the yacht was refitted in Greece, and the swimming pool covered over and converted into a mess room. She is said to have plied the waters between North Africa and Europe as a kind of VIP ferry

Olesen does not record further details about the negotiations, but we can imagine that they would have been as tense and complex as those for the previous training ship. “Admiral Abdul Dairi and his staff came to Copenhagen to sign the contract which he and I had already agreed in Baghdad. He arrived, merrily declaring that he had been explicitly ordered by President Saddam Hussein not to sign anything, unless we would give an extra five per cent discount as well as 10 large buses and four Mercedes-Benz cars as a sign of goodwill.”

A number of fruitless meetings ensued, before the Admiral declared he would return home without a signature. “He often ordered his adjutant to immediately book a flight home to Baghdad, which meant the meeting was over.” Olesen reluctantly accepted the new terms over the phone, and a final meeting was convened the next morning in a Copenhagen hotel. “Of course, they did not get a five per cent price reduction, or 10 buses, or the four Mercedes, but they did include a modest amount for spare parts.”

The presidential suite had a barber's chair intended for keeping Saddam Hussein's moustache in tip-top condition

The actual price of the deal for the new presidential yacht was never disclosed, but the rumour circulating in Iraq is that the yacht cost $25 million (£11m at 1980 rates). What is sure, however, is that the shipyard made a thumping loss on the order, due in no small part to the constant interference from Iraqi officials. “They demanded unrealistic changes and improvements without extra [fees] or extensions to the deadlines,” says Tenna Bülow, archivist of the Elsinore Museum.

The specifications for Hussein’s yacht were lost when the yard pulled down the shutters for the last time in 1983, but we know it was sumptuously fitted out. There were 14 guest cabins accommodating up to 28, and quarters for a generous 35 crew. The key feature was undoubtedly the presidential suite, which occupied the full beam of the boat and included an office and a dedicated barber’s chair intended for keeping the president’s trademark moustache in tip-top condition. The centrepiece was a vast fairy-tale bed hung with curtains and a rich canopy. Silk carpets, gold leaf, elaborate panelling and Louis XV-style chairs completed an image of extraordinary ostentation.

The presidential suite’s bed that caused a diplomatic incident after an “infidel” shipyard employee dared to touch it

The presidential suite’s bed that caused a diplomatic incident after an “infidel” shipyard employee dared to touch it

The bed was nearly the source of a diplomatic incident on delivery day. “It tempted one of the shipyard’s marine superintendents beyond his powers of resistance, and he sat down on [it],” says Bülow. “At the same time, one of the Iraqis walked through the door. The situation developed in a serious manner, not only because a shipyard employee had dared to touch the president’s bed, but because he was an infidel.”

The bedspread was removed and a replacement ordered from Paris at great expense. Amazingly, the superintendent was allowed to take the despoiled cover home, where he used it on his own bed for many years. It is now a star exhibit at the Elsinore Museum.

In view of the effort and treasure expended on Project 423, it is ironic that the Iraqi dictator never actually spent a night aboard. The yacht had by now been named Qadissiyat Saddam, referencing a mythical battle between Iraqi Arabs and the larger Persian army in the seventh century. It was a projection of power against the backdrop of the Iran-Iraq war, which had begun the year before, in 1980. At first the yacht was moored in Basrah, but when Iranian forces advanced along the lower Tigris in 1986, she was hurriedly sent to safety in the Saudi royal port of Jeddah on the Red Sea.

And there she remained until Saddam’s bloody regime was toppled by the American-led invasion in 2003. The yacht had apparently been well maintained alongside the Saudi royal fleet, with a permanent crew of 12. At some point during those 17 years, the Saudis began to consider the boat as their property and it was renamed al-Yamamah (“the dove”). Then, when Saddam was run to earth in 2006, the yacht was shifted to Aqaba, the only port of regional ally Jordan.

The terms of the transfer appear murky – was it a gift or was the yacht lent? This question resurfaced in 2007, when she appeared for sale in Nice with a £17 million price tag. By now she was called Ocean Breeze and photos depicted the lavish interior, in particular the dead dictator’s opulent suite, but there was little interest from buyers.

The new Iraqi government was on the lookout for the billions of dollars that Saddam had plundered, so the ambassador to France raised the alarm when he read of the yacht being up for sale. “He called on me to deploy all necessary measures to obstruct this transfer and seize this vessel on behalf of the Republic of Iraq,” says Maître Amir-Aslani, the country’s lawyer in Europe. Nice’s commercial court duly ordered that the yacht should be seized on 31 January 2008, pending a hearing about ownership.

We now know that the yacht had been put up for sale by a Cayman Island entity. “Sudeley Capital was an offshore company, whose capital was held by another offshore company, whose ultimate economic beneficiary was the King of Jordan,” explains Amir-Aslani.

“Inside was a hidden room - you cannot see it unless you know where it is”

In early February 2008, police and a bailiff boarded the yacht to search for evidence of its true owner. They found an insurance document, issued by Lloyd’s of London, in the name of an Iraqi official. “Nobody disputed that the original owner was indeed Saddam Hussein and therefore the Iraqi state,” continues Amir-Aslani. “We did not provide proof of the ownership of this boat as such, but we did provide the Iraqi constitution which showed that the assets of the state could not be transferred to others. And in any case, the opposing party had no documents either.”

The court ruled in July that the yacht belonged to the Iraqi people, and Sudeley decided to take the issue no further. Government spokesman Ali al-Dabbagh announced that the yacht, now called Basrah Breeze, would be smartened up and sold.

She steamed to Piraeus in Greece for a repaint and cosmetic work. While the idea may have been sound, the timing was not, and the global economic downturn intervened. Oil prices plummeted, credit dried up and, by spring 2009, the reported $30 million asking price looked optimistic. After sitting forlornly at anchor off Nice for a year, Basrah Breeze was recalled to Iraq in 2010 by the Ministry of Transport. “The Iraqi government’s decision to bring the yacht home will spare Baghdad the possibility of facing other claims and saves it docking and crew costs,” the ministry announced. The French sojourn had nevertheless cost $2 million in legal, crew and refit fees.

That November, Iraqi transportation minister Amer Abdul-Jabbar boarded the yacht for its triumphant entry into Basrah. “The return of the yacht means that the people’s will is stronger than the tyrant’s,” he proclaimed to crowds from the deck. “Saddam Hussein built this yacht to be used for his own personal purposes, but here it is returned to the Iraqi people.”

However, those same Iraqi people were unsure what to make of their new toy, according to a report by local journalist Ali Abu. While some hoped the yacht could be used for weddings and banquets, and the minister was proposing a ferry service for well-heeled businessmen or pilgrims, many were more concerned with reliable access to water and electricity. Abu quotes a University of Basrah student saying: “Life here will still be the same with or without [the yacht].”

Ironically, Basrah Breeze was placed under the care of the university, where it has served since 2014 as an unlikely research vessel for the Marine Science Centre. I ask the former director of the centre, Ali Douabul, about its reported missile defence system and escape sub. “That is a bit of exaggeration,” he says. But the ship has yielded up some secrets. “We were sitting in the big mess room and one of my students pushed something – it opened a thick door in the panelling.

“We can only allow two people at a time to stay on board. That’s all that we can afford”

Inside was a room that was completely hidden – you cannot see it unless you know where it is. I slept in this room one night.” Douabul has also dared to sleep in the presidential bed – during its only scientific expedition to date, in 2015. “The bed had never been used,” he laughs. “Modestly, I like to say that I am the first guy to sleep in it. I should have taken my wife with me, but I went with a lot of passengers and scientists instead.” During the trip, he charged guests who wanted to try the bedroom $10, “just for a joke”.

The yacht is ill-suited to science work, as it showed during the 10-day expedition to explore parts of the Gulf where coral had been rediscovered.

“We took a smaller ship as our research vessel and used it for the divers, because the yacht is very high, so they can’t dive from it. We used the yacht as a kind of mothership.” Another problem is its running costs, which are far too expensive for a hard-pressed university in a country with only 58 kilometres of coastline. “Even when we go on a very short trip, like we did in 2015, it cost me a fortune,” laments Douabul. “Imagine that we went 50 to 60 kilometres and then came back – we spent something in the neighbourhood of 60 tonnes of fuel.”

Fresh water is just as precious, and the boat also requires costly maintenance. The MTU engines are said to be sound, but the hull is in dire need of a scrape-down and repaint, while the air-con is full of holes. “We can only allow two people at a time to stay on board,” says Douabul. “That’s all that we can afford.” According to a quote from a nearby Iranian shipyard, the hull work alone could cost $1.5 million – money that just isn’t available. There is nowhere in Iraqi waters with the capacity to lift an 82 metre yacht. Various schemes to make better use of the yacht have been floated over the years. In 2018, it was widely reported that she had been relegated to a mere hotel for river pilots. “Completely wrong!” retorts Douabul. “If they’d used it for pilots, they would have ruined it in no time. It’s never been used as such. I got a very, very unpleasant call from the minister about that.”

Now there are hopes that the yacht will become a floating exhibit at the Museum of Basrah, housed in Saddam’s former palace. Director Qahtan Alabeed is developing a section of the museum devoted to local boatbuilding. “We want to reactivate work to rebuild a number of types of boats that sailed in the river and marshes,” he says. “We already have around 16.”

The palace gardens run down to the Shatt al-Arab waterway, where Alabeed wants to see the yacht moored permanently. Again, funding may prove the stumbling block. Alabeed says he has the support of the governor of Basrah and can “request any budget”. Douabul is doubtful. “Unfortunately, the main conclusion is: look at this criminal bloody Saddam who spent so much money on this yacht. If only he [used the money] to build 100 factories and provided work for people.

“If you ask me, the government has been misled to take this yacht, because they don’t have the ability to use it properly or commercially,” continues Douabul. “They thought it might be worth $200 million – I don’t know where they got their figures

from.”

Now he believes that the only solution lies outside Iraq. “Perhaps an international organisation like the International Maritime Organization should take care of it, because Iraqis will not. Then it becomes world heritage.”

AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

THE REST OF SADDAM'S FLEET

Saddam Hussein got better use from al-Mansur, built in 1983 by Finland’s Wärtsilä. The 121.1-metre yacht (pictured, top) was designed by Knude Hansen and had a 10-metre-high glass-domed atrium, a banqueting room to seat 200, a garage containing limos and a helipad and hangar.

Twin 12,000hp engines could propel the 7,539-tonne yacht to 20 knots. With a crew of 60 to look after 20 guests in 10 cabins, she was designed to project the dictator’s power. She was bombed in 2003 by the US Air Force, but in testament to her build, she didn’t sink. The burnt-out hulk was finally scuttled three years later, and the wreck chokes the Shatt al-Arab waterway to this day.

A smaller 60-metre river yacht was also built at Helsingor Vaerft for use on the Tigris in Baghdad itself. Described as “not beautiful” by yard MD Esmann Olesen, it was nevertheless finished to a luxurious level and had 58mm-thick polycarbonate windows to protect from snipers. Its fate is unknown.